The "Tiferet Yisrael Synagogue" in Jerusalem

Attractions in the Jewish Altstad-viertel of Jerusalem

The images can be enlarged

Short information

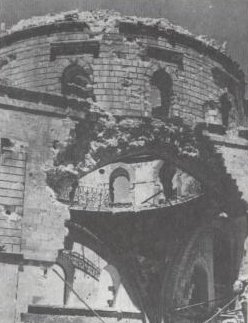

1835 started the construction of this synagogue; , 37 years later it was opened; 1948 it was destroyed by the Jordanians. Today it is just a ruin.

Detailed information

If the big Hurva platz departing eastwards, you reach the Tiferet-Strasse, one of the new, very busy shopping streets of the Jewish Quarter. Just after a few meters, take a side staircase to the top, on which one the remains of the synagogue "Tiferet Yisrael" achieved (Glory of Israel). The Tiferet Yisrael synagogue was one of the most important synagogues in the Old City of Jerusalem, before the Arab by the Jordanians in 1948 -israeli schen War was destroyed. It is named after Rabbi Israel Friedman of Ruzhin, but was also known as "Nissan Beck School" known after its founder Rabbi Nissan Beck. Although the Hasidim arrived in Jerusalem in the year 1747, Rabbi Nissan Beck began only in 1839 with his plans for a Hasidic synagogue. Until then, the devout had prayed Israel Beck's house in small, private places such as Rabbi. In the 1830s, learned Rabbi Israel Friedman of Ruzhin that Tsar Nicholas I intended in the Jewish Quarter of Jerusalem's Old City to build a church. Rabbi Friedman, who was very involved in supporting the Yishuv, instructed Rabbi Nissan Beck to thwart the plan of the tsar. Beck worked tirelessly to acquire the property, which intend to buy the Russians themselves. In 1843 he finally succeeded by the greatest effort.The Czar was forced to acquire another plot of land and then bought the site on the day of the Russian Compound is. In his anger he let Rabbi Friedman of the country point. When Rabbi Friedman in 1851, died, his son Rabbi Abraham Jacob Friedman of Sadigura the task continues to collect the necessary funds for the project of the synagogue building. The construction of the synagogue began in 1857. First, the Ottoman authorities denied the building permit, and has been identified as an Islamic grave, there were other problems. But the Muslim mayor allowed to relocate the grave outside the city walls. Once the foundations had been dug up, there was another setback. It became clear that one had caught up with a building permit from the Turkish authorities, but they were not keen to grant permission. But Rabbi Beck, an Austrian national, Franz Joseph I was persuaded by Austria to mediate and so was in 1858 the construction approved by the Turkish authorities. On his trip to the inauguration of the Suez Canal Franz Joseph I. in 1869 came to Jerusalem and visited the unfinished synagogue. Since he was working to protect and promote the rights of his subjects in the Holy Land, he pays 1,000 francs to finance the construction of the dome. The three-story synagogue in 1871 was completed and inaugurated on August 19, 1872, 29 years after the Land had been purchased. For the next 75 years the Tiferet Yisrael synagogue served as a center of the Hasidic community in Jerusalem. During the War of Independence in 1948 the Jordanian Legion captured the Old City of Jerusalem and the synagogue, which had served as a defense post for the defenders of the Jewish Quarter. An hour after midnight it was blown up to 21. May 1948 in the night of the 20th. Since that time, the synagogue stands in ruins since. Source: Wikipedia

The Tiferet Yisrael Synagogue (c) Wikipedia

The Tiferet Yisrael Synagogue (c) Wikipedia

The Tiferet Yisrael Synagogue (c) Wikipedia

The Tiferet Yisrael Synagogue (c) Wikipedia

The Tiferet Yisrael Synagogue (c) Wikipedia

The Tiferet Yisrael Synagogue (c) Wikipedia

Information panel to Tiferet Yisrael Synagogue (c) 2011 www.theologische-links.de

Today ruins of the Tiferet Yisrael Synagogue - looking to the east (c) 2011 www.theologische-links.de

Today ruins of the Tiferet Yisrael Synagogue - looking to the West (c) 2011 www.theologische-links.de

Jerusalem Tour to the Jewish Quarter

The Old and New Jewish Quarter in the Old CIty of Jerusalem - Destructuion and Reconstruction

During the reign of the kings of Judah in Jerusalem the city grew considerably and its neighborhoods included the western hill – the present-day location of Mt. Zion and the Jewish Quarter. During the Second Temple period the “upper city” of Jerusalem was where the city’s dignitaries lived. They built splendid homes and the remains of these structures fill us with wonder, even now, when we observe them two thousand years later.

The destruction of the Temple, the exile and the Roman and Byzantine rule brought with them a period of crisis and times when there were no Jews living in Jerusalem. But with the Muslim conquest in the 7th century CE the Jews returned to Jerusalem. The Crusader conquests in 1099 dealt a serious blow to the Jewish community in the city, and it was restored only at the end of the 12th century, with the return of the Muslim rulers to Jerusalem. At first Jews lived on Mt. Zion, but beginning with the 14th century the Jews began to concentrate in the area that constitutes the present Jewish Quarter.

Photo: Ron Peled

For the 400 years of Ottoman rule in Jerusalem there was a Jewish community living inside the walls of the Old City. The community, which we call the “Old Yishuv,” was not a single, cohesive unit.

Until the middle of the 19th century the community consisted mainly of Sephardic Jews, descendants of the exiles from Spain and others. Beginning with the mid-18th century Ashkenazi Jews begin to settle in the city, but not for extended periods. There were a few individuals who came to Israel gradually, or groups of Hassidim and Talmud scholars. In 1721 Ashkenazi settlement in Jerusalem ceased, and was only renewed 90 years later. In the 19th century Jerusalem’s Jewish population grew significantly, and towards the end of the century Jews began an “exodus” from the walled city. This chapter of history ends with the fall of the Jewish Quarter to the Jordanians in the War of Independence. Following the Six Day War, with the reunification of Jerusalem in 1967, archaeological excavations were undertaken in the city.

These excavations revealed fascinating discoveries, evidence of Jewish life in various historical periods. Afterwards, the homes of the Jewish Quarter were refurbished and Jews are living here once again.In this tour we will visit some of the ancient sites of Jerusalem: synagogues, the courtyards and institutions of the “Old Yishuv” in the Jewish Quarter.

The winding streets of the Quarter are lined with charitable and social institutions, houses of worship and remnants of the past that convey the hopes of so many Jews who left their homes and came to Jerusalem with a single prayer in their hearts, “If I forsake thee, O Jerusalem…”

King David’s Gate – Zion Gate

The bullet holes we see on the façade of the gate are indicative of the battles that took place here during the War of Independence, at the end of which the Jewish Quarter fell into Jordanian hands. From 1948 until the Six Day War the border was here: Mt. Zion was under Israeli control while the Old City was in Jordanian hands. In Arabic the gate is called Bab a-Nebi Daoud – the Gate of King David, because it connects the Old City with Mt. Zion which, according to Jewish, Muslim and Christian tradition, is the location of King David’s tomb.

Below us is Gan HaTekuma (Garden of Renewal) adjacent to the Old City walls. The garden contains remains of one of the largest churches in Jerusalem from the Byzantine period (325-638), the Nea Church (Greek for “new”).

Photo: Ron Peled

“From out of the depths…” – The Four Sephardic Synagogues

Following the expulsion from Spain at the end of the 15th century, many Jews began to arrive in

Jerusalem, but the Yochanan Ben Zakkai Synagogue was only established in the 17th century. The other synagogues – “Eliahu Hanavi” (Elijah the Prophet), “HaEmtza’i” (the “middle” synagogue) and the “Istanbuli” (Istanbul) – were built alongside.

The four synagogues were built below street level, apparently due to the prohibition imposed by the Ottoman rulers against building houses of worship higher than mosques. A community center has developed around the synagogues. Since 1892 (5653) the Sephardic chief rabbi – the Rishon LeZion – has been inaugurated at the synagogue. Near the window at the top of the southern wall, the synagogue’s “treasure” was hidden: a shofar and an oil flask, which are said to be from the Temple. At the End of Days, Elijah the Prophet will come and blow the shofar, and with the

oil in the flask he will light the Eternal Flame on the Temple Mount.

Renewal and Comfort – Batei Mahse Square

In 1860, when the crowding and lack of housing in Jerusalem reached crisis level, a neighborhood for the poor people of Jerusalem was built at the initiative of the Kollel Hod (Holland und Deutschland). This Jewish organization, whose members were from Holland and Germany, built houses that could be leased at low cost, or even for free, in order to make it easy on the city’s scholars and poor. The original Mishmarot HaKehuna St.

02-6280592 Sun.-Thurs. 9:00-16:00, Fri. 9:00-13:00, Entrance fee , Recommended that you call ahead for reservations

batei mahse (sheltered housing) were built at the southern end of the square. After several years the Rothschild Family erected another building for the same purpose, and it remains standing today on the western side of the square. The crest of the Rothschild Family can still be seen on the building’s façade. The apartments of the batei mahse were luxurious by the standards of the time, and families who lived there were considered very fortunate.

When the Jewish Quarter surrendered after the War of Independence the Quarter’s residents and defenders gathered in the square and from there exited through the Zion gate. That was on Friday, May 28, 1948.

The top floor of the building houses the offices of the Jewish Quarter Development and Reconstruction Company.

Photo: Gad Rize

Days of Siege – The Monument

During the War of Independence the Jewish Quarter was cut off from Jerusalem’s other Jewish neighborhoods and was under siege. Since the Quarter’s residents could not leave the city to bury their dead on the Mount of Olives, they asked for permission to bury them inside the city. On this site 48 of the Jewish Quarter’s residents and fighters were buried, including 10 yearold Nissim Gini, the youngest IDF casualty, who took part in defending the Jewish Quarter. Following the Six Day War the remains of these casualties were moved and reinterred in a mass grave on the Mount of Olives.

We pass by the Beit El Yeshivat HaMekubalim (Yeshiva of the Kabbalists), which was founded in Jerusalem by Rabbi Gedalia Hayon in 1733. The original yeshiva building was damaged in the War of Independence, and the present building was constructed after the Six Day War. Opposite us is the Hurva Synagogue, and next to it is the Ramban Synagogue. Entrance to the synagogues is from HaYehudim Street (see map).

Marble columns and a beautiful dome – The Ramban Synagogue

In 1267 Rabbi Moshe Ben Nachman (1194-1270), known as Nachmanides or the Ramban, visited Jerusalem, where he met only two Jews who worked as painters. The Ramban was saddened at the sight of the devastated city and he described what he saw in a letter to his son: “Great is the neglect and vast is the destruction… The entire Temple is utterly ruined, Jerusalem is thoroughly destroyed… And we found a house in ruins built with marble columns and a beautiful dome and we took it to the synagogue because the city is abandoned and anyone who wishes to take from the ruins can help himself.” The Ramban Synagogue was apparently built on Mt. Zion, where the Jews of Jerusalem had lived previously, and was moved here when the Jews entered the Jewish Quarter in the 14th century. For many years this was the only synagogue in the city, and it matches the description given by Rabbi Ovadia of Bartenura (1440-1530) during his visit to Jerusalem in the 15th century: “The synagogue in Jerusalem is built upon columns, and it is long and narrow and dark, and it has no light except from a single opening, and inside there is a water cistern.” The synagogue was closed in 1589 by order of the Ottoman ruler, and reopened

for prayer in 1967, on the 700th anniversary of the Ramban’s visit to Israel.

Photo: Ron Peled

From destruction to construction – The Hurva Synagogue

On Wednesday, the first day of Cheshvan in the year 5461 (October 1700), Rabbi Yehuda the Chassid came to Jerusalem leading a group of his students. They resided in the Ashkenazi

area and planned to build a synagogue nearby.

But on Shabbat Rabbi Yehuda fell ill, and on the following Monday, just a few days after his arrival in Jerusalem, he passed away.

His followers were left without a leader and without the donations that had been promised to

their rabbi, but were slow in coming. Although the followers did, in fact, complete the construction of the synagogue they were left in serious debt. In 1721 their Arab creditors stormed the courtyard and the synagogue, destroying them both. The community members were forced to leave Jerusalem, and for 90 years the Ashkenazi Jews dared not show their faces in Jerusalem for fear that this would be detrimental to them.

Since that time the courtyard was known as the Hurva of Rabbi Yehuda HaChassid (i.e., “the ruin”).

The debt was repaid only many years later, at the beginning of the 19th century. In 1837 students

of the G’ra (the Ga'on of Vilna) built the Menachem Zion synagogue in the courtyard, and in 1856, the main synagogue of the Perushim community (followers of the Vilna Ga’on) in Jerusalem was dedicated. It was a large and impressive edifice, known as Beis Ya’akov. Despite the size and splendor of the building, the name “Hurva” stuck, as a reminder of the original destruction that took place at the site.

In May 1948 the synagogue was blown up by soldiers of the Arab Legion. After the Six Day War the question of renovating and rebuilding the Hurva Synagogue was raised, but renovations began only 40 years after the city’s reunification.

Today visitors can once again be impressed by the grandeur and power of the synagogue building.

We recommend visiting the Old Yishuv Court Museum (see map), which tells the story of the Jewish Quarter’s residents from the 16th century until the fall of the Jewish Quarter in 1948. It is the story of vibrant and creative life under conditions of material deprivation, while living under foreign rule.

Shopping in Byzantine Jerusalem – the Cardo

We are walking upon the main street of RomanByzantine Jerusalem. The street runs north-south

and is called the Cardo Maximus. It was a broad street, 22 meters wide, with two rows of columns on either side and lined with small shops and stalls. As we walk along the Cardo we can see theoriginal paving stones.

Inside a covered alley there is a mosaic map on the wall. This is a reproduction of a section of the Madaba Map, which was part of a mosaic floor discovered in the 19th century at the Church of St. George in the city of Madaba (Medba) in Jordan. The mosaic depicts the Holy Land, and gives us a rare glimpse of Byzantine Jerusalem during the 6th century. On the map we can clearly see the Cardo with its two rows of columns, the Church of the Holy Sepulcher, the Nea Church, and many other structures.

Photo: Ron Peled

Farther along the Cardo is an exhibition entitled "Alone on the Walls", which presents the struggle of the Jewish Quarter during the War of Independence through rare documentary photos taken by the photographer John Philips. The site also has a unique film that tells the story of the battle as

it is etched in the memories of the Jewish Quarter’s defenders and its residents.

Against the Assyrian Army – the Broad Wall

In the archaeological excavations carried out following the Six Day War, a wall was discovered here that had been part of the city’s northern fortifications during the First Temple Period. The wall was built during the reign of King Hezekiah who rebelled against the Assyrian Kingdom.

Construction of the wall was carried out as part of the king’s preparations for the siege by Senacherib the

King of Assyria: “And you numbered the houses of Jerusalem, and you broke down the houses to fortify the wall” (Isaiah, 22:10). The remains of the houses upon which the wall was built can be seen beneath us, in the section to the west of the wall.

Photo: Ron Peled

Journey to Biblical Jerusalem – Ariel, The Center for the History of First Temple Jerusalem, Yad Ben Zvi

Ariel is a visitor center that illustrates the sites and happenings of Jerusalem during biblical times. There is a model that recreates the city at the end of the First Temple Period – houses, the walls, the king’s palaces and the Temple. The institute presents a multimedia show entitled The Spirit of the Stone, which depicts the secret of the city’s magic during the times of the kings and prophets.

Opposite us, in the basement of the modern apartment building is the Israelite Tower, a fortification from the First Temple Period. On this site archaeologists found three Babylonian arrowheads, testifying to the city’s destruction by the Babylonians in the 586 BCE. The site is closed to visitors.

From glory to destruction – the Tiferet Yisrael Synagogue

The Tiferet Yisrael Synagogue (also known as the Nissan Beck Synagogue) was built by the Ashkenazi Hassidic community in the middle of the 19th century, and it is named for the Great Rabbi Yisrael of Radzine.

For many years the synagogue remained without a dome. In 1869 Emperor Franz Josef of the AustroHungarian Empire visited the synagogue. When he asked why the synagogue had no dome, he was told that the synagogue had doffed its hat in honor of the emperor.

Photo: Ron Peled

Franz-Joseph was so impressed with the clever response that he donated the funds needed to finish building the synagogue dome. Construction of the synagogue was completed in 1872 but it was destroyed by the Jordanians during the War of Independence.

The Herodian Quarter – Wohl Archaeological Museum

In the archaeological excavations carried out here following the Six Day War remains were found of opulent houses, including the Palatial Mansion, dating from the Herodian Period (about 2,000 years ago). These houses apparently belonged to families of priests and they are designed in Roman-Hellenistic style with various Jewish touches.

Of particular note is a carving of a menorah that was found on one of the walls, the only evidence remaining from the days of the Temple.

Visitors may receive an audio guide free of charge for a self-guided tour of the museum.

1 Hakara’im St. 02-6265902, Sun.-Thurs., 9:00-17:00, Fri. 9:00-13:00, Entrance fee

Photo: Ron Peled

Katros House – The Burnt House

These are the remains of a house that we destroyed when Jerusalem was captured and destroyed by the Romans. At the site there is an interesting multimedia presentation depicting the life of the Katros family, a family of wealthy priests, and the human and tragic drama that reflects the reality of life in Jerusalem during the Second Temple Period.

2 Tiferet Yisrael St., 02-6265902, Sun.-Thurs., 9:00-17:00, Fri. 9:00-13:00, Entrance fee

My heart is in the east – The Western Wall

We are looking towards the Temple Mount, the holiest site of the Jewish people. Here, according to tradition, the world was created and this is where Abraham came to sacrifice Isaac. It is here that King Solomon built the First Temple approximately 3,000 years ago, and where those returning to Zion from Babylon built the Second Temple.

During the 1st century BCE King Herod renovated the Second Temple. The platform that Herod built atop the Temple Mount was surrounded by gigantic support walls. The Western Wall is what remains from one of these support walls. Its original height was about 30 meters and it was about half a kilometer long.

Photo: Ron Peled

In the 16th century the Western Wall was first used by Jews as a place of worship, a symbol of their longing and yearning for the Holy Temple. In the years when Jerusalem was divided (1948-1967) visits to the Western Wall were prohibited.

Many Jews came to Mt. Zion, to King David’s Tomb in order to look towards the Temple Mount from the rooftop – with the hope of some day returning to the Western Wall to pray. Following the Six Day War masses of people thronged to the Wall, and today as well, thousands upon thousands of people visit the site, which has become a central focus for the Jewish people.

This is where we conclude our journey through the alleyways of the past in the Jewish Quarter. Adjacent to the Western Wall are sites that reveal even more layers of Jerusalem’s history, and those who are interested can continue and visit them (see the tour, “Jerusalem in the First and Second Temple Periods”).

The Ancient Domes of Jerusalem

7 Comments

True Jerusalem. These are the true domes of Jerusalem, not the Al Aqsa mosque that most people think of today. Thanks to Israel Daily Picture.

This picture of the two domes of the Hurva and Tiferet Yisrael Synagogues in Jerusalem’s Old City

But we never came across a photo with such clarity, suggesting that the archives at UC-Riverside contains the original photos taken by the Underwood & Underwood Co. in 1900. UC-R’s files also allow huge and detailed on-screen enlargements of the photos. We thank the heads of the library for permission to republish their photos, and we abide by their request to limit the photos’ sizes on these pages.

[…]

Avraham Shlomo Zalman Hatzoref arrived in Eretz Yisrael 200 years ago and was responsible for building the Hurva synagogue. Ashkenazic Jews had been banned from the Old City in the early 19th century after defaulting on a loan. Hatzoref, a student of the Gaon of Vilna and a builder in Jerusalem, arranged for the cancellation of the Ashkenazi community’s large debt to local Arabs. In anger, local Arabs killed him in 1851. (Hatzoref is recognized by the State of Israel as the first victim of modern Arab terrorism.)

The two prominent synagogue domes shared the panoramic view of Jerusalem with the domes of the Dome of the Rock and al Aqsa Mosque for almost 80 years. In the course of the 1948 war, the Jordanian army blew up both buildings and destroyed the Jewish Quarter of the Old City.

The Dome of the Rock was a supremacist project by the leader of the Muslim world in the first half of the twentieth century. Amin al Husseini made the dome his special project. It had fallen into a state of utter disrepair, but al-Husseini saw it to his political advantage to restore it.

The dilapidated Dome of the Rock was a decaying old relic well into the 20th century. It was of no import and it was no longer used as a place of worship. When the calls for a Jewish state were reverberating throughout the world, the annihilationist leader of the Muslim world and Hitler ally, Mufti al Husseini, realized that he had to create a territorial fiction in order to deny the Jewish people their holiest site.

It was that vicious Jew-hater, the Mufti Al Husseini, who undertook the gold plating of the dome (above right) and the making of improvements to the Al Aqsa mosque.

This served the purpose of enhancing the importance of Jerusalem in the Islamic world; up until that point, it had been an insignificant religious backwater for Muslims. Photos of Jerusalem before this time show a relatively colorless and nondescript dome on top of the Temple Mount (more here).

The Hurva Synagogue today stands off a plaza in the centre of Jerusalem’s Jewish Quarter. Excavations carried out at the site in July and August 2003 revealed evidence from four main settlement periods: First Temple (800–600 BCE), Second Temple (100 CE), Byzantine and Ottoman.[8] Three bedrock-hewn mikvahs (ritual baths) were uncovered there dating from the 1st century.[9] The earliest tradition regarding the site is of a synagogue existing there at the time of the 2nd-century CE sage Judah haNasi.[10] By the 13th century, the area had become a courtyard, known as Der Ashkenaz (the Ashkenazic Compound),[6]for the Ashkenazic community of Jerusalem.[11] In 1488, Obadiah ben Abraham described a large courtyard containing many houses for exclusive use of the Ashkenazim, adjacent to a “synagogue built on pillars,” referring to the Ramban Synagogue.[12] The Ramban Synagogue had been used jointly by both Ashkenazim and Sephardim until 1586, when the Ottoman authorities confiscated the building. Thereafter, the Ashkenazim established a synagogue within their own, adjacent courtyard.[6]

-------

The dilapidated Dome of the Rock was a decaying old relic well into the 20th century. It was of no import and it was no longer used as a place of worship. When the calls for a Jewish state were reverberating throughout the world, the annihilationist leader of the Muslim world and Hitler ally, Mufti al Husseini, realized that he had to create a territorial fiction in order to deny the Jewish people their holiest site.

It was that vicious Jew-hater, the Mufti Al Husseini, who undertook the gold plating of the dome (above right) and the making of improvements to the Al Aqsa mosque.

This served the purpose of enhancing the importance of Jerusalem in the Islamic world; up until that point, it had been an insignificant religious backwater for Muslims. Photos of Jerusalem before this time show a relatively colorless and nondescript dome on top of the Temple Mount (more here).

The Hurva Synagogue today stands off a plaza in the centre of Jerusalem’s Jewish Quarter. Excavations carried out at the site in July and August 2003 revealed evidence from four main settlement periods: First Temple (800–600 BCE), Second Temple (100 CE), Byzantine and Ottoman.[8] Three bedrock-hewn mikvahs (ritual baths) were uncovered there dating from the 1st century.[9] The earliest tradition regarding the site is of a synagogue existing there at the time of the 2nd-century CE sage Judah haNasi.[10] By the 13th century, the area had become a courtyard, known as Der Ashkenaz (the Ashkenazic Compound),[6]for the Ashkenazic community of Jerusalem.[11] In 1488, Obadiah ben Abraham described a large courtyard containing many houses for exclusive use of the Ashkenazim, adjacent to a “synagogue built on pillars,” referring to the Ramban Synagogue.[12] The Ramban Synagogue had been used jointly by both Ashkenazim and Sephardim until 1586, when the Ottoman authorities confiscated the building. Thereafter, the Ashkenazim established a synagogue within their own, adjacent courtyard.[6]

|

| The UC-R photo bears no caption or date on this picture of the Tiferet Yisrael Synagogue(Credit: Keystone-Mast Collection, California Museum of Photography at UCR ARTSblock, University of California, Riverside) |

William H. Seward, who served as President Abraham Lincoln’s secretary of state, visited Jerusalem in 1859 and 1870. He wrote a travelogue after his second trip, and he described attending Friday night services at the “Wailing Wall” and in one of the two impressive synagogues. Seward’s description appears below.

We present below interior pictures of the two synagogues from the UC-R and Library of Congress collections.

|

| The interior of the Tiferet Yisrael Synagogue (circa 1900) (Credit: Keystone-Mast Collection, California Museum of Photography at UCR ARTSblock, University of California, Riverside) |

|

| Interior of the Hurva Synagogue (circa 1900) (Credit: Keystone-Mast Collection, California Museum of Photography at UCR ARTSblock, University of California, Riverside) |

Note the curtains covering the Ark containing the Torah scrolls. When the German Emperor arrived in Jerusalem in 1898, the Jewish community constructed a welcome arch, photographed by the American Colony photographic department. The curtains from the synagogues and the Torah crowns were taken down to decorate the arch.

|

| Interior of the Hurva Synagogue (circa 1898, American Colony Photograph Department, Library of Congress). Note the curtain, enlarged below |

|

| The Hurva interior in the 1930s. The curtain is dedicated in memory of Hanna Feiga Greerman, the daughter of Mordechai. The bima inscription reads “Generous gift of Yisrael Aharon son of Nachman known as Mr. Harry Fischel and his wife Sheina daughter of Shimon [?] of New York.” Fischel died in January 1948. |

Click on photos to enlarge. Click on captions

to view the original pictures.

Secretary of State William Seward’s Friday Prayer

Was it in the Hurva or the Tiferet Yisrael Synagogue?

Excerpt from Travels around the World

to view the original pictures.

Secretary of State William Seward’s Friday Prayer

Was it in the Hurva or the Tiferet Yisrael Synagogue?

Excerpt from Travels around the World

… [After leaving the Wailing Wall] a meek, gentle Jew, in a long, plain brown dress, his light, glossy hair falling in ringlets on either side of his face, came to us, and, respectfully accosting Mr. Seward, expressed a desire that he would visit the new synagogue, where the Sabbath service was about to open at sunset. Mr. Seward assented.

|

| William H. Seward, Lincoln’s Secretary of State |

A crowd of “the peculiar people” attended and showed us the way to the new house of prayer, which we are informed was recently built by a rich countryman of our own whose name we did not learn. It is called the American Synagogue. It is a very lofty edifice, surmounted by a circular dome. Just underneath it a circular gallery is devoted exclusively to the women. Aisles run between the rows of columns which support the gallery and dome. On the plain stone pavement, rows of movable, wooden benches with backs are free to all who come.

At the side of the synagogue, opposite the door, is an elevated desk on a platform accessible only by movable steps, and resembling more a pulpit than a chancel. It was adorned with red-damask curtains, and behind them a Hebrew inscription. Directly in the centre of the room, between the door and this platform, is a dais six feet high and ten feet square, surrounded by a brass railing, carpeted; and containing cushioned seats. We assume that this dais, high above the heads of the worshippers, and on the same elevation with the platform appropriated to prayer, is assigned to the rabbis.

We took seats on one of the benches against the wall; presently an elderly person, speaking English imperfectly, invited Mr. Seward to change his seat; he hesitated, but, on being informed by [Deputy U.S. Consul General] Mr. Finkelstein that the person who gave the invitation was the president of the synagogue, Mr. Seward rose, and the whole party, accompanying him, were conducted up the steps and were comfortably seated on the dais, in the “chief seat in the synagogue.” On this dais was a tall, branching, silver candlestick with seven arms.

At the side of the synagogue, opposite the door, is an elevated desk on a platform accessible only by movable steps, and resembling more a pulpit than a chancel. It was adorned with red-damask curtains, and behind them a Hebrew inscription. Directly in the centre of the room, between the door and this platform, is a dais six feet high and ten feet square, surrounded by a brass railing, carpeted; and containing cushioned seats. We assume that this dais, high above the heads of the worshippers, and on the same elevation with the platform appropriated to prayer, is assigned to the rabbis.

We took seats on one of the benches against the wall; presently an elderly person, speaking English imperfectly, invited Mr. Seward to change his seat; he hesitated, but, on being informed by [Deputy U.S. Consul General] Mr. Finkelstein that the person who gave the invitation was the president of the synagogue, Mr. Seward rose, and the whole party, accompanying him, were conducted up the steps and were comfortably seated on the dais, in the “chief seat in the synagogue.” On this dais was a tall, branching, silver candlestick with seven arms.

The congregation now gathered in, the women filling the gallery, and the men, in varied costumes, and wearing hats of all shapes and colors, sitting or standing as they pleased. The lighting of many silver lamps, judiciously arranged, gave notice that the sixth day’s sun had set, and that the holy day had begun. Instantly, the worshippers, all standing, and as many as could turning to the wall, began the utterance of prayer, bending backward and forward, repeating the words in a chanting tone, which each read from a book, in a low voice like the reciting of prayers after the clergyman in theEpiscopal service. It seemed to us a service without prescribed form or order. When it had continued some time, thinking that Mr. Seward might be impatient to leave, the chief men requested that he would remain a few moments, until a prayer should be offered for the President of the United States, and another for himself. Now a remarkable rabbi, clad in a long, rich, flowing sacerdotal dress, walked up the aisle; a table was lifted from the floor to the platform, and, by a steep ladder which was held by two assistant priests, the rabbi ascended the platform. A large folio Hebrew manuscript was laidon the table before him….

- See more at: http://pamelageller.com/2014/01/the-ancient-domes-of-jerusalem.html/#sthash.2NWBCxmI.dpuf

For more

information on the Internet:

information on the Internet:

Tiferet Yisrael Synagogue (c) Wikipedia (English)

No comments:

Post a Comment